Part two of my interview with Tony Fitzgerald, Innovation Scientist, covering how modern science now explains why my therapeutic methods work.

Transcript

Is mental health science meeting physical health science?

Lilian Sjøberg1: I'm really happy to hear that at least one part of science is catching up, updating. Have you met scientists that work with disease, what you can call physical diseases? Have you met anyone? Because even Gabor Mate2 does not touch a lot into that. Have you met anyone that makes the connection that it is actually also the case for chronic diseases?

Tony Fitzgerald3: That's a good question. I've been working mostly in the psychology, psychiatry, and psychotherapy space. There are many, many, many. It's a massive growing area like PTSD. PTSD is now understood in those terms. Anxiety is now understood in those terms. There are these models applied to all these, psychopathology, depression, and so on. So, there's a massive wealth of evidence in the psychology area. I don't look a lot in the disease space. What I have come across is a medical doctor, for who chronic pain is now understood as a predictive process.

LS: I can tell you it's the same with Parkinson's and MS. I've also worked with a woman with something called burning mouth syndrome. The general opinion is that it's valid for 90 percent of all diseases as well. So, the only thing we need to get rid of is the mental vs physical nonsense.

TF: It does apply to the body and the brain, right? Working together.

LS: You cannot take out the happiness of you or the sadness. It's sort of all over. So, you cannot separate it as we thought in the old model.

Prediction theory as the missing link between physical and mental health - in regard to explaining symptoms

TF: Yeah. Disease. I haven't worked a lot in that space. But when I listen to Gabor Mate, and he hasn't moved to this prediction realm yet, but you can see as he speaks that underlying predictions going on that then can contribute to those illnesses.

LS: I think it's a matter of wording. I'm glad about this predicting theory because it's given me a search word. Gabor Mate and I come from a world where we have experienced it and helped people, and then there's you as a scientist that suggests that we use these words to describe the same.

So, it's more a matter of getting the same language, for the things I do, and the things Gabor does to get the same result. Because when I have been doing searches, I can think of I didn't know that keyword. I'm of course on my second language. It doesn't help me in being creative, but I wouldn't use the wording on the things I do. But I can see that it's a matter of language. How do we describe things?

TF: Yes. I absolutely agree. It's important to kind of come to a common language and understanding, otherwise there's always going to be differences. I've discussed this with some psychological colleagues who are interested in the health space as well. And our understanding, our feeling was that once the kind of psychological sciences update across that kind of widespread “institutional space”, then we're kind of looking at a sort of “psychology 3.0”.

If you think 1.0 was kind of like Freud or someone just having a theory. No, not a great deal of science. A lot of observation, moving to people like Peter Levine or somatic experiencing where there is now an observation, but also some science to support it, but it's a slice of science. And my colleague, Philip Lowe, was talking about psychology 3.0, which is now when we understand in this model. Right. Where things make sense, you now have a different option. This technique seems to work.

Why does it work? We don't know. Let's find out. Let's try and get some science to explain it. It's like, well if this is how the brain works, it updates itself if the predictions don't match. How can we use that to then provide a therapy that takes people through three simple steps, and they update their behaviour, their emotional reaction, their level of stress. And it's done at the brain level that generates the stress. So, it's no longer being generated.

Creating an understandable methaphor

It was like a car with a wobbly tire and you're trying to drive the car straight. But the wobbly tire keeps pulling you off. That's like the stress. If you take it to the garage and get the wheel aligned, which is the equivalent of changing these predictions. Now it's not creating that emotional stress system anymore. Now that the car drives straight, you don't have that stress response.

So, the body stays in a healthier condition and then there's less opportunity for disease. It's more able to repair itself without that extra load.

LS: I think I have to go into that metaphor. I like metaphors because a lot of people are visual. So having a metaphor and just to give my take on it, being on my second language, I cannot be very, very detailed in my opinion. But if you have this car with this wheel that's wobbly, you can say that's sort of the mental thing, the trauma that's causing that. But then maybe the wobbling was not so big that this car needed to go for repair when it was “a teenager or young adult”, then driving with a wobbling car for 30, 40, or 50 years will explain why other parts of the car get out of whack because it's been bumping.

And so that's where you could say the physical disease comes in. That the effects of being in a little stress long term. Not so much stress, so you get referred to a mental hospital when you are a teenager, but a little less stress and smaller traumas that after a long life driving with this wobbly wheel will get the body into a state where other things are not working perfectly.

Again, if you can get this car, a new wheel and meant the old trauma.

TF: And yeah, that makes a lot of sense. I like how you can explain that with the body, right? That over time, these things that I think you probably look up allostatic load.

LS: I didn't know that word, but people say, “Why do I get it when I'm 50 or 60 or 70 years old?” I say you didn't have wrinkles when you were 30. Things happen. We get older and things get more visible.

TF: So, the concept you have described is known in the science. It's called allostatic load4. And we'll talk about how when there's ongoing allostatic predictions, ongoing allostatic needs for survival and hyper vigilance and affected sleep and all these sorts of patterns around abandonment or those little patterns of fear of rejection, all those bits and pieces. Yeah. I need to be perfect, or I need to be a certain way to be accepted. All those sorts of drivers, you said, drive that car into a certain shape, and it's not a healthy shape and that extra stress now falls down. Cortisol systems and immune systems and these other really important aspects of the body fall apart. And once they all start to sort of fall apart, become a bit more systemic. And that's when you start to run into issues.

LS: If you have big traumas and come to a doctor, they know that this is mental, something big happened to you. But when it's a little smaller, things that are not good enough, I work too hard on my job, then I get a divorce. Nothing, maybe not a lot of big things, but a pile of things that add up, and then suddenly you get the same result. And then you come to the doctor and say, what's going on here? And unless you start crying and speaking up about all these problems, the doctor says, OK, this is a physical disease. We'll send you to a neurologist and figure it out.

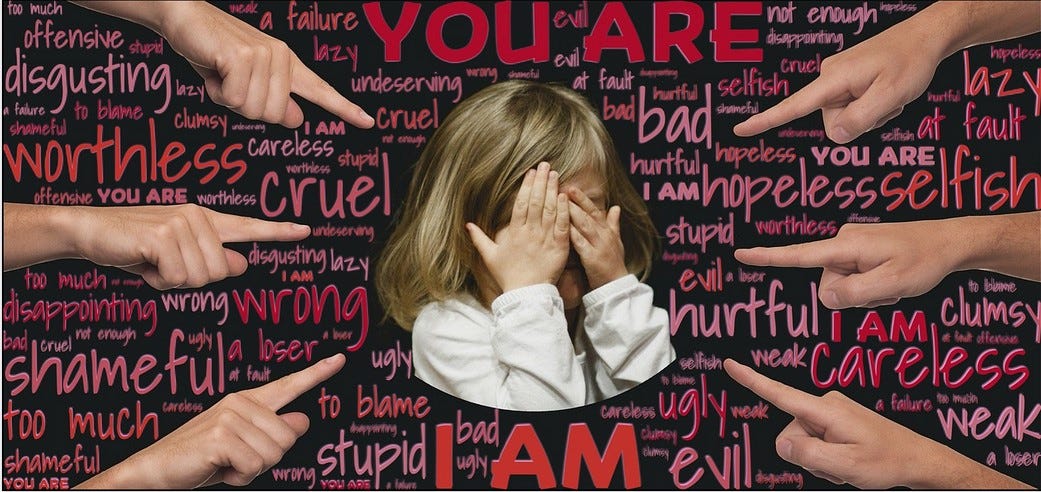

TF: Yeah, I think that's it. That there's an understanding now in the science literature of how these things play out over time. But as you said, it doesn't seem to have crossed into the medical fraternity yet that these small traumas, and even most people don't consider this is I think this is the key. Most people don't consider them traumas, right? To feel like you were smacked as a child, and you had to comply. Most people see that as normal. Right. But now in the science, it shows there are so many repercussions of that type of parenting, of controlled parenting, of abusive or controlling parenting. There is so much evidence now in the literature that kind of tracks how that it’s almost like with the ACE score5, the ACE [Adverse Childhood Experiences] studies. And it's almost like that on a slightly lowest level or even that sort of one ACE, a couple of aces, or even just sub-ACE, but those play out like the ACE study just shows.

LS: It's so easy. The younger you are, when you experience things, the harder the impact.

TF: Yes, as a child, and I think that this is where the prediction system starts to become a game changer in understanding diseases. Because those predictions your brain is making drive aversive states. So, all your behaviors are set up around “I can't feel rejected, or I can't feel shame” because this is what's been conditioned into me. But understanding from a prediction point of view that over a long period of time can then drive these behaviors of imperfectionism or addiction, workaholism, that type of addiction. And those then lead to a body that starts to break down over time.

I think my kind of feeling is this psychology 3.0, this understanding of the brain's prediction machine, how those young, very young, early experiences, young in life drive these predictions over time. And as Gabor Mate talks about mostly, right, it's the authenticity6. So, authenticity versus attachment is one of the biggest ones. And once you can start to understand that that plays out over time and how those predictions become bodily experiences, experienced repetition in whatever you got conditioned to as a child repeats as an adult, but in that adult sphere. And the way you interpreted it back then has not been good enough. That interpretation just becomes an expected version of yourself in the world as a prediction.

And so, it plays out in your behavior, in how you beat yourself up, in how you become frustrated yourself, how you are disappointed in yourself or worry that other people will be disappointed in you. Those are all predictions and they've come from these early childhood experiences.

When you look at them as predictions, now you can see there's a link to the past. Yeah. And not just a link, but actually a difference in the present that we can use to help the person update. Because you're not that child, you're not in that environment anymore in a new environment with new skills.

You've learned much, much more in that time. Plus, you have access to a larger cognitive ability. So, you can actually allow that to create updates in those predictions and then you don't have the experience of not good enough anymore. You know, the fear of disappointing others.

You now have a different prediction in your car and your tire that goes, I can be straight, I can fail. It's OK. It's not a shame. It's normal, natural shame, but it's not conditioned to rejection anymore. Yeah. I don't need to fear being rejected.

I can always accept myself. If others don't accept me, then that's up to them. So, you start to your whole behavior start to shift and you can do that through this prediction system. I'm sure the way you work as well with people, it shifts those perceptions, it shifts those predictions, and once you've done that now, you don't have that stress load, you have that fear load.

Lilian Sjøberg: I am a biologist and therapist that help people with chronic diseases get back on track again - most on my clients have Parkinson’s disease. By dissolving the division between mental ane physical, all these people can get help. I have for the last 7 years dedicated my time experimenting: What happen if we let go of the impossible (=the lure of a cure that per definition can only come in a pill form, but never does), and instead do the possible and reduce stress on people with chronic disease. Being persistent and very nerdy we can help people. This interview is building a bridge between mental and physical health.

Dr. Gabor Maté: renowned addiction expert, speaker and author. Dr. Gabor Maté is one of the worlds leading thinkers on trauma, addiction, stress and childhood development. One of the few I have found is making the connection with mental and physical health

Dr Tony Fitzgerald (PhD). For the past 20+ years he has continually researched science and innovation, working in Universities and Hospitals in Cambridge, London, Leeds, Brisbane and Perth. He is dedicating his time and enthusiasm to translating the latest neuroscience of how our brains construct our inner world to make a difference in mental health.

Allostatic load refers to the cumulative burden of chronic stress and life events. It involves the interaction of different physiological systems at varying degrees of activity. When environmental challenges exceed the individual ability to cope, then allostatic overload happens as a result - and that gives you mental problems as well as physical symptoms. See this post:

Symptoms As Alarm Calls from the Inside

Another subject we need to talk about is: What is a symptom? We often say we have 5 sensory inputs: touch, taste, smell, hearing, and seeing. You can call them the dashboard of your body. They give a lot of signals to you all day long. Just sit down with a cup of coffee and start to tune in to these, e.g. try sensing where your clothes touch your skin, s…

Adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years). For example: experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect. witnessing violence in the home or community.

Authenticity means you're true to your own personality, values, and beliefs, regardless of the pressure that you're under to act otherwise. You're honest with yourself and with others, and you take responsibility for your mistakes. Your values, ideals, and actions align.